Black Sun, The Battle of Summit Springs, 1869

Black Sun, The Battle of Summit Springs, 1869 Lay the Mountains Low

Lay the Mountains Low Black Sun: The Battle of Summit Springs, 1869 (The Plainsmen Series)

Black Sun: The Battle of Summit Springs, 1869 (The Plainsmen Series) Dance on the Wind tb-1

Dance on the Wind tb-1 Death Rattle tb-8

Death Rattle tb-8 The Stalkers

The Stalkers Crack in the Sky tb-3

Crack in the Sky tb-3 Trumpet on the Land: The Aftermath of Custer's Massacre, 1876 tp-10

Trumpet on the Land: The Aftermath of Custer's Massacre, 1876 tp-10 A Cold Day in Hell

A Cold Day in Hell Long Winter Gone: Son of the Plains - Volume 1

Long Winter Gone: Son of the Plains - Volume 1 Buffalo Palace

Buffalo Palace Cries from the Earth

Cries from the Earth Death Rattle

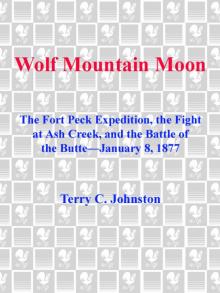

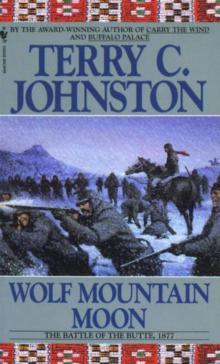

Death Rattle Wolf Mountain Moon: The Battle of the Butte, 1877 tp-12

Wolf Mountain Moon: The Battle of the Butte, 1877 tp-12 Crack in the Sky

Crack in the Sky Wolf Mountain Moon

Wolf Mountain Moon Turn the Stars Upside Down: The Last Days and Tragic Death of Crazy Horse

Turn the Stars Upside Down: The Last Days and Tragic Death of Crazy Horse Winter Rain

Winter Rain Shadow Riders: The Southern Plains Uprising, 1873 (The Plainsmen Series)

Shadow Riders: The Southern Plains Uprising, 1873 (The Plainsmen Series) Buffalo Palace tb-2

Buffalo Palace tb-2 Cries from the Earth: The Outbreak Of the Nez Perce War and the Battle of White Bird Canyon June 17, 1877 (The Plainsmen Series)

Cries from the Earth: The Outbreak Of the Nez Perce War and the Battle of White Bird Canyon June 17, 1877 (The Plainsmen Series) Shadow Riders, The Southern Plains Uprising, 1873

Shadow Riders, The Southern Plains Uprising, 1873 Ashes of Heaven (The Plainsmen Series)

Ashes of Heaven (The Plainsmen Series) Ashes of Heaven

Ashes of Heaven Devil's Backbone: The Modoc War, 1872-3

Devil's Backbone: The Modoc War, 1872-3 Wind Walker tb-9

Wind Walker tb-9 Trumpet on the Land

Trumpet on the Land Long Winter Gone sotp-1

Long Winter Gone sotp-1 Dying Thunder

Dying Thunder Seize the Sky sotp-2

Seize the Sky sotp-2 Winter Rain jh-2

Winter Rain jh-2 Cry of the Hawk jh-1

Cry of the Hawk jh-1 Sioux Dawn, The Fetterman Massacre, 1866

Sioux Dawn, The Fetterman Massacre, 1866 Sioux Dawn: The Fetterman Massacre, 1866 (The Plainsmen Series)

Sioux Dawn: The Fetterman Massacre, 1866 (The Plainsmen Series) Ride the Moon Down

Ride the Moon Down Ride the Moon Down tb-7

Ride the Moon Down tb-7 Red Cloud's Revenge

Red Cloud's Revenge Wind Walker

Wind Walker Black Sun, The Battle of Summit Springs, 1869

Black Sun, The Battle of Summit Springs, 1869 Lay the Mountains Low

Lay the Mountains Low Black Sun: The Battle of Summit Springs, 1869 (The Plainsmen Series)

Black Sun: The Battle of Summit Springs, 1869 (The Plainsmen Series) Dance on the Wind tb-1

Dance on the Wind tb-1 Death Rattle tb-8

Death Rattle tb-8 The Stalkers

The Stalkers Crack in the Sky tb-3

Crack in the Sky tb-3 Trumpet on the Land: The Aftermath of Custer's Massacre, 1876 tp-10

Trumpet on the Land: The Aftermath of Custer's Massacre, 1876 tp-10 A Cold Day in Hell

A Cold Day in Hell Long Winter Gone: Son of the Plains - Volume 1

Long Winter Gone: Son of the Plains - Volume 1 Buffalo Palace

Buffalo Palace Cries from the Earth

Cries from the Earth Death Rattle

Death Rattle Wolf Mountain Moon: The Battle of the Butte, 1877 tp-12

Wolf Mountain Moon: The Battle of the Butte, 1877 tp-12 Crack in the Sky

Crack in the Sky Wolf Mountain Moon

Wolf Mountain Moon Turn the Stars Upside Down: The Last Days and Tragic Death of Crazy Horse

Turn the Stars Upside Down: The Last Days and Tragic Death of Crazy Horse Winter Rain

Winter Rain Shadow Riders: The Southern Plains Uprising, 1873 (The Plainsmen Series)

Shadow Riders: The Southern Plains Uprising, 1873 (The Plainsmen Series) Buffalo Palace tb-2

Buffalo Palace tb-2 Cries from the Earth: The Outbreak Of the Nez Perce War and the Battle of White Bird Canyon June 17, 1877 (The Plainsmen Series)

Cries from the Earth: The Outbreak Of the Nez Perce War and the Battle of White Bird Canyon June 17, 1877 (The Plainsmen Series) Shadow Riders, The Southern Plains Uprising, 1873

Shadow Riders, The Southern Plains Uprising, 1873 Ashes of Heaven (The Plainsmen Series)

Ashes of Heaven (The Plainsmen Series) Ashes of Heaven

Ashes of Heaven Devil's Backbone: The Modoc War, 1872-3

Devil's Backbone: The Modoc War, 1872-3 Wind Walker tb-9

Wind Walker tb-9 Trumpet on the Land

Trumpet on the Land Long Winter Gone sotp-1

Long Winter Gone sotp-1 Dying Thunder

Dying Thunder Seize the Sky sotp-2

Seize the Sky sotp-2 Winter Rain jh-2

Winter Rain jh-2 Cry of the Hawk jh-1

Cry of the Hawk jh-1 Sioux Dawn, The Fetterman Massacre, 1866

Sioux Dawn, The Fetterman Massacre, 1866 Sioux Dawn: The Fetterman Massacre, 1866 (The Plainsmen Series)

Sioux Dawn: The Fetterman Massacre, 1866 (The Plainsmen Series) Ride the Moon Down

Ride the Moon Down Ride the Moon Down tb-7

Ride the Moon Down tb-7 Red Cloud's Revenge

Red Cloud's Revenge Wind Walker

Wind Walker