- Home

- Terry C. Johnston

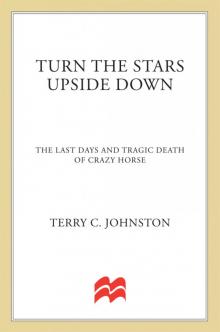

Turn the Stars Upside Down: The Last Days and Tragic Death of Crazy Horse

Turn the Stars Upside Down: The Last Days and Tragic Death of Crazy Horse Read online

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the author’s copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

Title Page

Copyright Notice

Dedication

Cast of Characters

On Crazy Horse

Map

Foreword

Prologue

Chapter One

Chapter Two

Chapter Three

Chapter Four

Chapter Five

Chapter Six

Chapter Seven

Chapter Eight

Chapter Nine

Chapter Ten

Chapter Eleven

Chapter Twelve

Chapter Thirteen

Chapter Fourteen

Chapter Fifteen

Chapter Sixteen

Chapter Seventeen

Chapter Eighteen

Chapter Nineteen

Chapter Twenty

Chapter Twenty-One

Chapter Twenty-Two

Chapter Twenty-Three

Chapter Twenty-Four

Chapter Twenty-Five

Chapter Twenty-Six

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Chapter Thirty

Chapter Thirty-One

Chapter Thirty-Two

Chapter Thirty-Three

Chapter Thirty-Four

Chapter Thirty-Five

Epilogue

Notes

Afterword

The Plainsmen Series by Terry C. Johnston

High Praise for the Work of Terry Johnston

About the Author

Copyright

Because he bravely stood and fought beside me over these past ten years, making possible the renaissance of my mid-life, I dedicate this sad tale of Crazy Horse’s final days to the warrior who has many times done battle at my shoulder, fighting victoriously so that my kids, Noah and Erinn, will now remain with their father until it’s time for them to spread their own wings and leave my nest. For my Montana-born Irish friend, “Seamus”—

I dedicate this book to

JAMES ROBERT GRAVES

CAST OF CHARACTERS

Seamus Donegan

Colin Teig Donegan

Samantha Donegan

OGLALA LAKOTA

Crazy Horse / Ta’sunke Witko

Worm / Waglu’la (father)

Black Buffalo Woman

They Are Afraid of Her (daughter)

Hump / Buffalo Hump

Little Big Man

Flying Eagle

Walking Eagle

Jumping Shield

Chips

No Water

Lone Bear

Red Cloud

Little Wound

Red Feather

Black Fox

Big Road

Little Hawk (brother)

Black Shawl (wife)

Little Hawk (uncle)

Young Man Afraid

He Dog

Eagle Thunder

Good Weasel

Looking Horse

Kicking Bear

Woman’s Dress

Little Wolf

Red Dog

American Horse

Shell Boy

No Flesh

BRULE / SICANGU LAKOTA

Spotted Tail

Black Crow

Good Voice

Swift Bear

White Thunder

Horned Antelope

MINNICONJOU / MNICOWAJU LAKOTA

Touch-the-Clouds

High Bear

MILITARY

Brigadier General George Crook—commander, Department of the Platte

Lieutenant Colonel Luther Prentice Bradley—commanding officer at Fort Robinson/commander of the District of the Black Hills

Major Julius W. Mason—Third U.S. Cavalry at Fort Laramie

Captain Daniel Webster Burke—commanding officer of Camp Sheridan

Captain James Kennington—Fourteenth U.S. Infantry

Lieutenant William Philo Clark / “White Hat”—military agent to the Oglala Lakota at Red Cloud Agency / chief of U.S. Indian Scouts (K Company, Second U.S. Cavalry)

Lieutenant John G. Bourke—aide-de-camp to General George Crook

Lieutenant Jesse M. Lee—agent to the Brule Lakota at Spotted Tail Agency

Lieutenant William Rosecrans—Fourth U.S. Cavalry

Lieutenant Henry L. Lemley—E Company, Third U.S. Cavalry

Private William Gentles—F Company, Fourteenth U.S. Infantry

Dr. Valentine T. McGillycuddy—Assistant Post Surgeon, assigned to Camp Robinson

CIVILIAN

Helen “Nellie” Laravie (“Chi-Chi”) (known among the Lakota as Brown Eyes Woman / Ista Gli Win)

Long Joe Laravie

Frank Grouard (Grabber)

Baptiste “Big Bat” Pourier

Dr. James Irvin—civilian agent at Red Cloud agency

Benjamin K. Shopp—special Indian agent

Lucy Lee

Billy Garnett

John Provost

Louis Bordeaux / Louis Mato

Joe Merrival—interpreter for Jesse M. Lee

The death of Crazy Horse was in short a tragedy just as Wounded Knee was; moreover it was a “tragedy” in the Shakespearean sense as well, for a great man was slain by a lesser man.

—BRIAN POHANKA

Time/Life Books

Although Red Cloud was not as skilled a politician [as Spotted Tail], he compensated for the shortcoming with a cunning ability to manipulate both the military and his own kindred. To maintain his prominence, Red Clould would remove any obstacle which posed a threat to his political aspirations.

—RICHARD G. HARDORFF

Crazy Horse: A Source Book

As the grave of [George Armstong] Custer marked [the] high-water mark of Sioux supremacy in the trans-Missouri region, so the grave of “Crazy Horse,” a plain fence of pine slabs, marked the ebb.

—LIEUTENANT JOHN G. BOURKE

On the Border with Crook

After [Crazy Horse’s] surrender he was made a hero by the army officers and shown much attention by the people generally. The agency Indians, becoming envious of Crazy Horse, told all manner of stories about him, and … false rumors.

—CHARLES P. JORDAN

former chief clerk at Red Cloud Agency

Red Cloud had reason to be jealous. Several times during the summer, he had been pushed aside while the prestige of Crazy Horse had been bolstered … Spotted Tail, too, was jealous of Crazy Horse and didn’t want him to go to Washington … [Crazy Horse] was sure in Spot’s acute understanding to be the lion of the delegation and to shadow and efface Spotted Tail in the public mind and diminish his influence as a chief.

—EDWARD KADLECEK

To Kill an Eagle

It is absurd to talk of keeping faith with Indians.

—GENERAL PHILIP H. SHERIDAN

At the time, and ever since, I held that the arrest and killing of the chief was unnecessary, uncalled-for and inexcusable. It was the result of jealousy, treachery and fear, and placing too much weight or reliance on reports that Crazy Horse was again contemplating joining Sitting Bull, still in British territory, there being a manufactured propaganda to that effect �

�

A combination of treachery, jealousy and unreliable reports simply resulted in a frame-up, and he was railroaded to his death.

—DR. VALENTINE T. MCGILLYCUDDY

in correspondence with author E. A. Brininstool

They could not kill him in battle. They had to lie to him and kill him that way.

—BLACK ELK

Black Elk Speaks

[Crazy Horse] trusted both sides—and then they killed him.

—LUTHER STANDING BEAR

My People the Sioux

FOREWORD

Despite all the rumor, half-truth, and fiction written about Crazy Horse, what little we do know about this mysterious man will forever be cloaked in legend.

Even as you gaze at the bloodied bayonet portrayed on the cover painting created for me by my old friend Lou Glanzman—America’s most prominent illustrator—there still rages some controversy over exactly how Crazy Horse’s life ended. Not only in seamy details of his “political” undoing by fellow Oglala leaders but also in the specifics of that very moment the death wound was inflicted. At that time, and even down to this day in some circles, it was believed that Crazy Horse actually stabbed himself with the knife he suddenly yanked from beneath the blanket hung over his arm in traditional fashion. To stab himself in the kidney, from behind, during a desperate struggle with his old friend Little Big Man?

As you look upon the cover artwork, ponder what sorts of covers have been on all the other books that seek to represent the death of Crazy Horse. And then remember that the last thing I want to write is a book about the surrender of this Oglala mystic. No, this is not a book about the surrender of Crazy Horse. While he did give his body over to the U.S. Army at Red Cloud’s agency in May of 1877, he did not turn over his mind, his heart, his warrior spirit. In the end, this is not a story of surrender, but a tale of triumph.

This is a story about how—despite all the efforts of the army officers and the white officials, along with many of Crazy Horse’s own Oglala people—this lone man succeeded in not surrendering everything that mattered most to him and, ultimately, what mattered most to the Lakota.

No, this is not a book about surrender. Instead, I have sought to tell you a story about the very personal victory of one solitary and misunderstood man.

Like other men of that dramatic era—men like George Armstrong Custer himself, who died an early and very human death, only to rise again as mythical and immortal—so too has Crazy Horse continued to live on, less as a man and more as a symbol of steadfast opposition to white dominance. It is not this legendary Crazy Horse I seek to write about. Others have already done so. Instead, it is the Crazy Horse who has not yet appeared in film, nor between the covers of a book—a flesh-and-blood Crazy Horse who is something less than mythic hero yet somehow more than mere man.

In the afterword that follows this tragic story, I list the many sources I relied upon to write this tale of surrender, betrayal, and murder. Despite all that has been put in print about this “Strange Man of the Oglala,” I found I had come to know very, very little about him from the written record. Instead, it took me walking the ground where Crazy Horse once stood, or fought, and where he ultimately died, before I felt I had come to some understanding of him … perhaps because he was so directly, so organically, tied to the land, his land, that his country—unlike what those of us who record our thoughts and hopes in print can ever say—will remain his one true legacy for all time.

Think of it. Standing in the shadow of Bear Butte, where most sources agree Crazy Horse was born. Sitting out on the barren, wind-battered end of what is now called Scotts Bluff in southwestern Nebraska, those heights generally accepted to have been the site of this man’s momentous and tragically prophetic vision quest. Walking through the calf-deep, icy snow crusted along the narrow ridgetop where Crazy Horse and the rest of his decoys lured Fetterman’s freezing, frightened soldiers for what would be this young warrior’s first great fight against the blue-coats. Stepping across the narrow strip of asphalt smeared atop Custer’s ridge, moving from that tall, stark monument to where we used to be allowed to stand and look down the slope to the north, imagining how Crazy Horse and his warriors raced around the base of this bluff to hurl themselves against the remnants of those five companies of U.S. cavalry punching north off the ridgetop, driven back to make their last stand in what took but minutes to become this war chief’s greatest victory against the blue-coats. Then you must trudge through the deep snow and January cold up a gradually rising bluff to reach the ridge where he and his last hold-outs suffered winter’s cruelest bite as a blizzard closed its maw on Battle Butte.… Don’t you sense despair seizing your heart like a hawk’s talons as you realize this was where Crazy Horse fought his last fight against the U.S. Army?

Eventually I find myself standing right outside the bolted door of this low-roofed log structure where few people come to intrude upon my thoughts while I stare at the ground, feeling like I’ve been kicked in the belly by the realization that it was right here that a bayonet was thrust into the body of Crazy Horse, that it was right next door that he took his last breath. That it was here that the great spiritual hoop of the Lakota people was irretrievably broken for all time.

Save for the Donegan family, all the rest of the characters in my story are real, and were there, on this very ground, during those final and fateful months of Crazy Horse’s life.

While a few of the scenes portrayed here may not have happened at all, or may not have happened as I have written them, you must bear in mind that I have attempted with the utmost fidelity to render this story just as true as I can make it, despite all the conflicting testimony from those who witnessed these final days.

Because Crazy Horse rarely spoke in public, even among his own people and especially in the presence of white men, little is left but the reminiscences of his friends, companions, and enemies. From them I have constructed the very psyche of the man I believe was this great Oglala chief—a man who had feet of clay, who had never desired the mantle of leadership to be laid about his shoulders, a man who wanted one woman but ended up settling for another, a father who wanted children of his own but in the end lost the only daughter we are certain he ever had. A man who weighed his obligations to his people against the hungers of his own soul.

So while not every scene in the book you are about to read may have actually occurred, I hope that by the time you close the covers on my story you will say to yourself that it had the ring of truth, perhaps saying to yourself that if we don’t really know exactly what happened to undo these last days of all that Crazy Horse was … then perhaps this short tale is how it might well have happened.

How Crazy Horse—this quiet Strange Man of the Oglala—emerged from some two decades of warfare to turn over his people and his weapons to the hated wasicu, and became mired in a tangle of events that he could not escape.

Perhaps this is how it happened.…

PROLOGUE

Pehingnunipi Wi

MOON OF SHEDDING PONIES, 1877

BY TELEGRAPH

ILLINOIS.

Crook on the Indians.

CHICAGO, May 2.—The Post has an interview with General Crook concerning the Indian question, the substance of which is that General Crook considers the Indians are like white men in respect to acquisitiveness; that if they are given a start in the way of lands, cattle and agricultural implements, they will keep adding to their wealth and settle down into respectable, staid citizens.

Ta’sunke Witko!

Oh, how he wanted to ignore that summons.

Ta’sunke Witko! Listen! For I am calling you, Ta’sunke Witko!

He finally opened his eyes into the cold, chill breeze of this springtime moon and looked around him, just to be sure one of his friends was not playing a child’s trick on him. No one. Which was as he preferred it, for he sat alone on the brow of this hill.

“You know me. I am the one called Ta’sunke Witko; I am Crazy Horse,” he sighed wear

ily, a pale streamer of his breathsmoke whipped away on a gust of wind. “Why do you come talk to me now, when you have not spoken to my heart in so many moons?”

A sudden sound erupted on the wind behind him, brushing his ears, like that of a rush of wings as a great bird settled behind him, coming to rest. Closer still—he sensed the being at his back, upon the crest of the hillside where he sat staring down into the valley where the sun would soon emerge. His people were awakening below, some of the old men kicking life into last night’s fires, old women starting into the brush to gather wood, the young boys leaving their blanket and canvas shelters, hunched over in the cold wind as they trudged out to the surrounding hills to bring in the first of the travois horses for their families and that day’s travel.

I have always been with you, Ta’sunke Witko. Even though I had no words to speak, I have never abandoned you.

“Then why has this felt like being so alone, if you truly were with me, Sicun?” he asked his spirit guardian.1

You are a man, so you are not always aware I am here. Sometimes … many times, your thoughts and your heart are so busy with other matters and feelings that it may seem as if I am not here with you. But … the truth remains that I am a part of you, and you a part of me until your final breath escapes your body. Until we are freed together.

“Why have you come to me now, Spirit Guardian?”

And he closed his eyes gently, imagining the majestic appearance of that spotted war eagle that was given birth inside his breast so many summers ago. The same Winged Being that had instructed him to wear no bonnet, only two feathers2 tied at the back of his long, sandy hair, their tips pointing down. The medicine pouch hanging from his neck contained the dried, shriveled brain and heart from the same golden, or spotted, eagle he had captured bare-handed in his youth, mixed with the petals and leaves of the wild aster. One of the eagle’s wing bones he had used to carve a whistle that he blew each time he raced into battle.

Didn’t you call me? Didn’t you make the climb up this hill in the cold darkness to talk to me?

“You know that I did.” Crazy Horse stared down at his hands, fingers interwoven together in his lap, his skin much lighter than that of most Lakota.3

Finally he raised his eyes to the horizon growing reddish orange below the purple bellies of the storm clouds that had soaked them all last night before lumbering off to the east with their fury. “But … how do I say the words that I have never spoken?”

Black Sun, The Battle of Summit Springs, 1869

Black Sun, The Battle of Summit Springs, 1869 Lay the Mountains Low

Lay the Mountains Low Black Sun: The Battle of Summit Springs, 1869 (The Plainsmen Series)

Black Sun: The Battle of Summit Springs, 1869 (The Plainsmen Series) Dance on the Wind tb-1

Dance on the Wind tb-1 Death Rattle tb-8

Death Rattle tb-8 The Stalkers

The Stalkers Crack in the Sky tb-3

Crack in the Sky tb-3 Trumpet on the Land: The Aftermath of Custer's Massacre, 1876 tp-10

Trumpet on the Land: The Aftermath of Custer's Massacre, 1876 tp-10 A Cold Day in Hell

A Cold Day in Hell Long Winter Gone: Son of the Plains - Volume 1

Long Winter Gone: Son of the Plains - Volume 1 Buffalo Palace

Buffalo Palace Cries from the Earth

Cries from the Earth Death Rattle

Death Rattle Wolf Mountain Moon: The Battle of the Butte, 1877 tp-12

Wolf Mountain Moon: The Battle of the Butte, 1877 tp-12 Crack in the Sky

Crack in the Sky Wolf Mountain Moon

Wolf Mountain Moon Turn the Stars Upside Down: The Last Days and Tragic Death of Crazy Horse

Turn the Stars Upside Down: The Last Days and Tragic Death of Crazy Horse Winter Rain

Winter Rain Shadow Riders: The Southern Plains Uprising, 1873 (The Plainsmen Series)

Shadow Riders: The Southern Plains Uprising, 1873 (The Plainsmen Series) Buffalo Palace tb-2

Buffalo Palace tb-2 Cries from the Earth: The Outbreak Of the Nez Perce War and the Battle of White Bird Canyon June 17, 1877 (The Plainsmen Series)

Cries from the Earth: The Outbreak Of the Nez Perce War and the Battle of White Bird Canyon June 17, 1877 (The Plainsmen Series) Shadow Riders, The Southern Plains Uprising, 1873

Shadow Riders, The Southern Plains Uprising, 1873 Ashes of Heaven (The Plainsmen Series)

Ashes of Heaven (The Plainsmen Series) Ashes of Heaven

Ashes of Heaven Devil's Backbone: The Modoc War, 1872-3

Devil's Backbone: The Modoc War, 1872-3 Wind Walker tb-9

Wind Walker tb-9 Trumpet on the Land

Trumpet on the Land Long Winter Gone sotp-1

Long Winter Gone sotp-1 Dying Thunder

Dying Thunder Seize the Sky sotp-2

Seize the Sky sotp-2 Winter Rain jh-2

Winter Rain jh-2 Cry of the Hawk jh-1

Cry of the Hawk jh-1 Sioux Dawn, The Fetterman Massacre, 1866

Sioux Dawn, The Fetterman Massacre, 1866 Sioux Dawn: The Fetterman Massacre, 1866 (The Plainsmen Series)

Sioux Dawn: The Fetterman Massacre, 1866 (The Plainsmen Series) Ride the Moon Down

Ride the Moon Down Ride the Moon Down tb-7

Ride the Moon Down tb-7 Red Cloud's Revenge

Red Cloud's Revenge Wind Walker

Wind Walker